Heroes of the British Empire in World War I

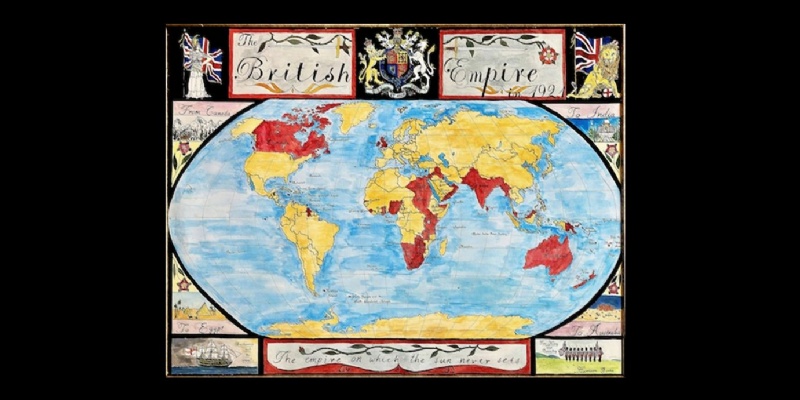

The contribution of nations within the British Empire was immense, and it is now generally accepted that without it, Britain would have found the conflict more difficult.

The contribution of nations within the British Empire was immense, and it is now generally accepted that without it, Britain would have found the conflict more difficult.

It is believed that the approximate number of soldiers is as follows:

- Canada 600,000

- Australia 400,000

- New Zealand 100,000

- South Africa 136,000

- India 1.5 million

- East and West Africa 120,000

- West Indies 16,000

For many decades after the First World War, the contribution of individuals to the conflict, especially if they were of non-white heritage, was largely ignored and hidden from history, and it has only been during the 21st century that this situation has started to change, enabling them to obtain the recognition they richly deserve.

Francis Pegahmagabow (Indigenous Canadian)

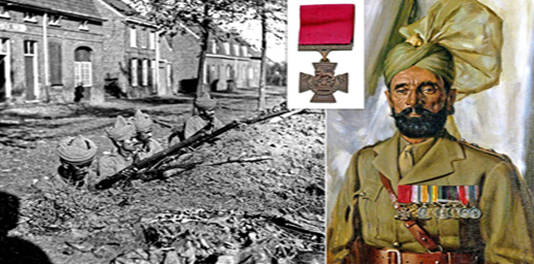

Khudadad Khan (India)

As recognition for his bravery and heroism, Khan became the first Indian soldier to be awarded the Victoria Cross, which was and remains the highest military honour for bravery and heroism in conflict. This recognition had the effect of encouraging more Indian soldiers to join the British Army and indicated the important role played by troops from across the Empire in supporting British troops in Europe at this time. Khan survived the conflict and after 1918 continued to serve in the British Indian Army and, following the independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, remained a respected individual in the latter, which became his new homeland. In the 21st century, Khan is still celebrated as a national hero in Pakistan because of the courage he displayed at Ypres in 1914 as well as elsewhere during the conflict, representing the contribution and sacrifices which were made by all Indian soldiers (over 1.5 million in total) during the First World War.

John Simpson Kirkpatrick (Australia)

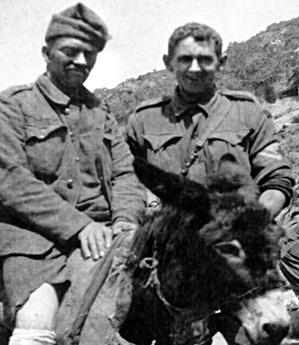

Although John Simpson Kirkpatrick was born in South Shields near Newcastle, his family moved to Australia and, with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, he enlisted with the Australian Imperial Force and was sent to Gallipoli in South Eastern Europe in 1915, where he became a stretcher bearer with his key role being to rescue wounded soldiers from the battlefield which was often very dangerous. Kirkpatrick did this with the use of donkeys to carry injured soldiers from the front line to field hospitals being under threat from machine gun and artillery fire. He often made several trips per day. The actions of Kirkpatrick saved the lives of many soldiers.

Although John Simpson Kirkpatrick was born in South Shields near Newcastle, his family moved to Australia and, with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, he enlisted with the Australian Imperial Force and was sent to Gallipoli in South Eastern Europe in 1915, where he became a stretcher bearer with his key role being to rescue wounded soldiers from the battlefield which was often very dangerous. Kirkpatrick did this with the use of donkeys to carry injured soldiers from the front line to field hospitals being under threat from machine gun and artillery fire. He often made several trips per day. The actions of Kirkpatrick saved the lives of many soldiers.

Kirkpatrick did not win any military honours for his actions but the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs) held him in high esteem, and he showed through his actions that heroism on the battlefield could take many forms and involved more than just military combat. Within a matter of a few weeks of being stationed at Gallipoli, Kirkpatrick was killed in action at the age of just 22. In the decades since his death, however, he has become a symbol of courage and humanitarianism because of his actions, and he is remembered in Australia for his willingness to put his own life at risk to save that of others even though he did not have to and being prepared to do so under extreme conditions.

Kirkpatrick did not win any military honours for his actions but the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs) held him in high esteem, and he showed through his actions that heroism on the battlefield could take many forms and involved more than just military combat. Within a matter of a few weeks of being stationed at Gallipoli, Kirkpatrick was killed in action at the age of just 22. In the decades since his death, however, he has become a symbol of courage and humanitarianism because of his actions, and he is remembered in Australia for his willingness to put his own life at risk to save that of others even though he did not have to and being prepared to do so under extreme conditions.

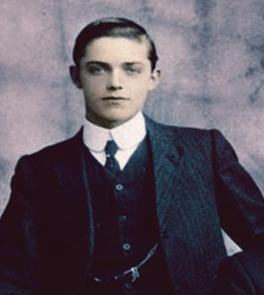

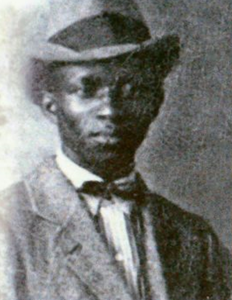

Lionel Fitzherbert Turpin (Guyana: West Indies)

Lionel Turpin was born in the British colony of Guiana (now Guyana) in 1896 before moving to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of the First World War, where there were better opportunities in terms of work than remaining in the Caribbean at that time. With the outbreak of conflict in 1914, Turpin volunteered to join the armed forces, wanting to demonstrate his loyalty to Britain and its Empire against Germany, hoping that such military service would provide greater opportunities for him. He joined the British Expeditionary Force, serving in the York and Lancaster Regiment and the King’s Royal Rifle Regiment, which saw active service on the Western Front. Much of Turpin’s early period in the armed forces was involved in training for military action, although by 1916 he saw action for the first time at the Battle of the Somme, where he displayed considerable bravery in spite of the fact that he had his lungs burned as a result of a gas attack.

Lionel Turpin was born in the British colony of Guiana (now Guyana) in 1896 before moving to the United Kingdom before the outbreak of the First World War, where there were better opportunities in terms of work than remaining in the Caribbean at that time. With the outbreak of conflict in 1914, Turpin volunteered to join the armed forces, wanting to demonstrate his loyalty to Britain and its Empire against Germany, hoping that such military service would provide greater opportunities for him. He joined the British Expeditionary Force, serving in the York and Lancaster Regiment and the King’s Royal Rifle Regiment, which saw active service on the Western Front. Much of Turpin’s early period in the armed forces was involved in training for military action, although by 1916 he saw action for the first time at the Battle of the Somme, where he displayed considerable bravery in spite of the fact that he had his lungs burned as a result of a gas attack.

Lance Corporal William Faulds (South Africa)

The contributions made by Faulds during the First World War and official recognition of them indicate that the First World War was a global conflict and did not just involve trench warfare on the Western Front in Europe. Many more African soldiers played a crucial role in the conflict on the continent. The leadership provided by Faulds in this region was important in enabling Britain to be successful in this area of the conflict. After the war, he returned to South Africa, where he was recognised for his bravery, although outside the country it has only been in recent decades that his efforts during the conflict have become more well-known.

Richard Charles Travis (New Zealand)

Richard Travis was born in 1884 and, before the First World War, worked as a horse trainer and farmworker, but when the conflict broke out in Europe in 1914, he enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, joining the Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment and after 18 months of training, his unit was sent to the Western Front in France in 1916 where New Zealand troops fought alongside British and Australian Forces. During his time on the Western Front, Travis developed a reputation for being one of the best scouts (looking for the enemy) and snipers in the New Zealand army. He became highly skilled at moving behind enemy lines, gathering details on German plans and destroying enemy machine gun positions. The bravery and leadership shown by Travis led to him being awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in 1917 for his action and he was mentioned in Dispatches for his “outstanding service.” His action helped save the lives of many soldiers by providing Allied forces with valuable intelligence and allowing his unit to plan safer attacks.

Richard Travis was born in 1884 and, before the First World War, worked as a horse trainer and farmworker, but when the conflict broke out in Europe in 1914, he enlisted in the New Zealand Expeditionary Force, joining the Otago Mounted Rifles Regiment and after 18 months of training, his unit was sent to the Western Front in France in 1916 where New Zealand troops fought alongside British and Australian Forces. During his time on the Western Front, Travis developed a reputation for being one of the best scouts (looking for the enemy) and snipers in the New Zealand army. He became highly skilled at moving behind enemy lines, gathering details on German plans and destroying enemy machine gun positions. The bravery and leadership shown by Travis led to him being awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in 1917 for his action and he was mentioned in Dispatches for his “outstanding service.” His action helped save the lives of many soldiers by providing Allied forces with valuable intelligence and allowing his unit to plan safer attacks.

In July 1918, during an Allied advance near Rossignol Wood in France, Travis led a small group of soldiers in an attack which destroyed several German machine gun positions which were holding up an Allied advance on the front line. This took place under heavy enemy fire. In addition, under the leadership of Travis, his unit managed to capture a number of German troops and clear their trenches, indicating great courage. For his actions he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Tragically, however, shortly after this success, Travis was killed by shellfire while inspecting the newly captured positions. The bravery displayed by Travis made him one of New Zealand’s most decorated soldiers during the First World War and, in addition to the Victoria Cross, he also received the Military Medal and the Distinguished Conduct Medal and was mentioned in Dispatches four times. As a result of his actions, he was respected by many of his fellow soldiers.

In July 1918, during an Allied advance near Rossignol Wood in France, Travis led a small group of soldiers in an attack which destroyed several German machine gun positions which were holding up an Allied advance on the front line. This took place under heavy enemy fire. In addition, under the leadership of Travis, his unit managed to capture a number of German troops and clear their trenches, indicating great courage. For his actions he was awarded the Victoria Cross. Tragically, however, shortly after this success, Travis was killed by shellfire while inspecting the newly captured positions. The bravery displayed by Travis made him one of New Zealand’s most decorated soldiers during the First World War and, in addition to the Victoria Cross, he also received the Military Medal and the Distinguished Conduct Medal and was mentioned in Dispatches four times. As a result of his actions, he was respected by many of his fellow soldiers.

Mr Goodall, Head of History and Politics